I have always had a horror of words that are not translated into deeds, of speech that does not result in action — in other words, I believe in realizable ideals and in realizing them, in preaching what can be practiced and then in practicing it.

Theodore Roosevelt

See this essay’s companion piece: “How to Successfully Reform a Bureaucracy: George Waring & the Department of Street Cleaning”

At the dawn of the Progressive era in the 1890s, “good government” politicians were sweeping municipal elections with an eye toward ending corruption and getting results. They wanted government to work, work fairly, and deliver.

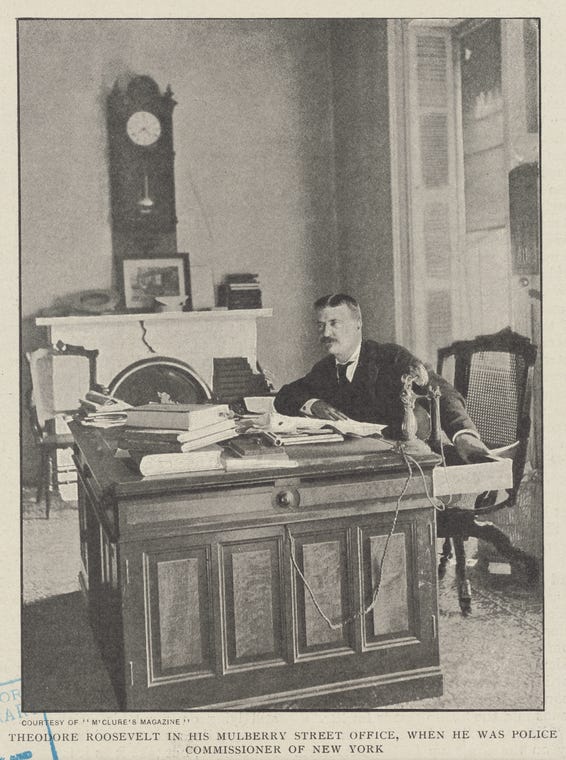

I’ve previously written about how George Waring modernized the New York City street sweeping department from 1895–1897, laying the groundwork for a clean New York today. This current piece is about what was going on in the New York City police department at the same time. It was headed by Theodore Roosevelt, who, like Waring, exerted a transformational effect on both his department and the city.

Roosevelt modernized the technological arsenal of the police, hired based on merit, and fought corruption consistently—against the poor and rich, the politically powerful and not, and across ethnicities.

What led up to Roosevelt’s appointment

The Lexow Committee

In 1894, the Republican-controlled state senate convened a special committee to investigate police corruption in New York City. It was chaired by Senator Clarence Lexow, and would eventually produce The Lexow Report, which threw the city into scandal:

Eventually 10,576 pages of testimony compiled from 678 witnesses made clear the price Tammany had exacted for protecting outlawed interests. Politicians and police officers had been systematically shaking down saloons, brothels, abortionists, and gambling dens. Some policemen justified the practice as a way of making back the money they had been forced to ante up to buy their jobs in the first place…Police corruption was matched by police lawlessness: investigators turned up evidence of involvement in counterfeiting and confidence scams, pervasive election frauds, voter intimidation, and the systematic brutalizing of newer immigrants…1

From page 15 of the Lexow Report itself:

…it has been conclusively shown that in a very large number of the election districts of the city of New York, almost every conceivable crime against the elective franchise was either committed or permitted by the police, invariably in the interest of the dominant Democratic organization of the city of New York, commonly called Tammany Hall.

The Reform Election of 1894

Driven by the success of the Lexow Report, a reform alliance led by Republicans and the city’s Chamber of Commerce successfully backed William Lafayette Strong for mayor in the November 1894 city elections. He had a dual mandate to run the city fairly and efficiently, and to restore moral order to the government.

…Strong was elected by a fusion alliance of Republicans and anti-Tammany Democrats in November 1894. The city was ready to “throw the bums out,” and it did; this was part of a larger wave that saw Republicans take unified control of the state government (governor, legislature, and most statewide offices), and cost Democrats control of both houses of Congress.2

After Strong was elected, he initially offered Roosevelt the job of street sweeping commissioner; when Roosevelt declined, he gave it to Waring. In Roosevelt’s own words:

Mayor Strong had already offered me the Street-Cleaning Department. For this work I did not feel that I had any especial fitness. I resolutely refused to accept the position, and the Mayor ultimately got a far better man for his purpose in Colonel George F. Waring.3

His judgement would prove to be correct in many ways. Waring was already in his early sixties when he assumed the commissionership of street cleaning (where as TR was only 36), and he had an accomplished career fit for purpose. Among many other things, he had: served as the chief drainage engineer for Central Park during its creation in the 1850s, designed the specialized sewer system for the city of Memphis, Tennessee, effectively served as a Union officer in the Civil War, and much more. He knew how to do the work of designing physical systems specifically related to cleanliness and hygiene, how to command men, and how to work within government.

Writing in a special 1915 edition of “The Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science” on the New York City government, Bronx Borough President Mathewson said:

Waring truly had no equal for efficacy, and his legacy in staff training and the physical plant of the street sweeping department would long outlast him. The same could not be said about many of Roosevelt’s police innovations, but Roosevelt would demonstrate the full range of his power later in his career, when he was closer to Waring’s age.

Roosevelt prior to NYPD

Roosevelt had a wildly different set of experiences, as well as a far more aggressive temperament. A native New Yorker, he’d served as a member of the New York State Assembly from 1881-1884, after which he “went west” and became a popular and best-selling author. He was particularly well known for Winning the West (1889) and his history of New York City (1891). When he returned east, President Benjamin Harrison appointed him to the federal civil service commission in 1889. Once on the federal civil service commission, he immediately turned his reform guns on his own party and president:

Then, without asking Harrison’s permission, Roosevelt impetuously went on an investigating tour of the President’s home state of Indiana and looked into the behavior of Harrison’s former law partner. TR’s impolitic travels made headlines and produced a “galvanic shock” in the newspapers because he struck out so swiftly wherever he found corruption.4

Despite the trouble he caused for Harrison, Roosevelt continued to serve on the civil service commission throughout his term, and was even reappointed by the Democratic victor of the 1892 presidential election, Grover Cleveland. After the 1894 New York City election, he returned to New York City as part of a grander plan to pursue higher office in the future.5

His strong morality, his brusque personality, and his belief in fair dealing and honest government colored his tenure with the New York City police.

Roosevelt as the President of the Police Board of Commissioners

Unlike Waring, who was alone at the head of his department, Roosevelt was one of four police commissioners on the New York City police board. They elected him as their president, and he governed the department like he was alone on the commission as much as possible. Later, when he was governor of New York State from 1899–1900, he would sign the state law that eliminated the board and replaced it with a sole police commissioner responsible to the mayor.

Roadblocks at the start

When Roosevelt fully began his work in May 1894, he hit two roadblocks: the distributed structure of the police board, and a lack of public trust in police reform. Regarding the police board structure, he spared no criticism (emphasis added):

The form of government of the Police Department at that time was such as to make it a matter of extreme difficulty to get good results. It represented that device of old-school American political thought, the desire to establish checks and balances so elaborate that no man shall have power enough to do anything very bad. In practice this always means that no man has power enough to do anything good, and that what is bad is done anyhow.

In most positions the “division of powers” theory works unmitigated mischief. The only way to get good service is to give somebody power to render it, facing the fact that power which will enable a man to do a job well will also necessarily enable him to do it ill if he is the wrong kind of man. What is normally needed is the concentration in the hands of one man, or of a very small body of men, of ample power to enable him or them to do the work that is necessary; and then the devising of means to hold these men fully accountable for the exercise of that power by the people. This of course means that, if the people are willing to see power misused, it will be misused. But it also means that if, as we hold, the people are fit for self-government—if, in other words, our talk and our institutions are not shams—we will get good government. I do not contend that my theory will automatically bring good government. I do contend that it will enable us to get as good government as we deserve, and that the other way will not.6

As if this weren’t enough, neither the public, city politicians, nor police officers had much confidence that he could affect reform:

It was of course very difficult at first to convince both the politicians and the people that we really meant what we said, and that every one really would have a fair trial. There had been in previous years the most widespread and gross corruption in connection with every activity in the Police Department, and there had been a regular tariff for appointments and promotions. Many powerful politicians and many corrupt outsiders believed that in some way or other it would still be possible to secure appointments by corrupt and improper methods, and many good citizens felt the same conviction.7

Roosevelt got the stiffest rebuff yet from the (soon to be outgoing) police chief:

The corrupt chief, Thomas F. Byrnes, told TR he had no chance to reform the system: “It will break you. You will yield. You are but human.”8

The only thing Roosevelt, or any politician, could do under these circumstances was deliver results. As with sanitation and street sweeping, people had heard unrealized calls for reform before.

Nevertheless, an astounding quantity of work was done in reforming the force. We had a good deal of power, anyhow; we exercised it to the full; and we accomplished some things by assuming the appearance of a power which we did not really possess.

So what did Roosevelt do as president of the police board?

Merit-based civil service exams for recruits

Roosevelt replaced bribes and political patronage positions with a merit-based civil service exam for new officers, and ended the “pay for play” practice that had been so thoroughly recorded by the Lexow commission—the “regular tariff” for appointments. And even as he had high standards for his recruits, he was unyielding in his practice of welcoming any kind of man into the force: “We paid not the slightest attention to a man’s politics or creed, or where he was born, so long as he was an American citizen; and on an average we obtained far and away the best men that had ever come into the Police Department.”9

Roosevelt also regularly railed against laws and procedure that made it difficult to remove under- or poor-performing police officers from their roles (emphasis added):

In the same way the Commissioners could appoint the patrolmen, but they could not remove them, save after a trial which went up for review to the courts. As was inevitable under our system of law procedure, this meant that the action of the court was apt to be determined by legal technicalities. It was possible to dismiss a man from the service for quite insufficient reasons, and to provide against the reversal of the sentence, if the technicalities of procedure were observed. But the worst criminals were apt to be adroit men, against whom it was impossible to get legal evidence which a court could properly consider in a criminal trial (and the mood of the court might be to treat the case as if it were a criminal trial), although it was easy to get evidence which would render it not merely justifiable but necessary for a man to remove them from his private employ — and surely the public should be as well treated as a private employer.10

But evaluating existing police officers, whether on the job or for promotions, was less straightforward than administering entrance exams. The promotional system relied upon character and capacity references from other officers, who could have been corrupt themselves. So what could one do?

Massive action in personally evaluating the police force

While Roosevelt investigated as many of these claims as he could, he also deployed far more of his time than his predecessors to simply watch his officers do their jobs. He did far more work, and took massive action. This approach transformed the police department:

[Roosevelt] delighted in making surreptitious nocturnal tours of the city, accompanied only by his friend (and publicist) Jacob Riis (whom Roosevelt had sought out after reading his Other Half). Dressed in black cloaks and wide-brimmed hats, the duo crept up on errant bluecoats sneaking beers in saloons, nabbing them while their mustaches were still drenched with incriminating foam.11

On one early morning patrol Riis took TR along First, Second, and Third Avenues, where they found one policeman asleep on a butter barrel and quite a few absent from their beats. Commissioner Roosevelt, with reporter Richard Harding Davis and Riis in tow, discovered a patrolman evading his duty seated in an oyster bar…The next day Roosevelt demoted the oyster bar dawdler, and word spread fast through the police force that the commissioner knew how to find loafers.12

Roosevelt created a credible threat of punishment for police officers who weren’t doing their duty, and that threat was often him personally catching them. This approach earned fear from slackers, and praise from the great mass of officers doing their job. He also won praise from the public:

…whistles in the shape of “Roosey’s teeth” were peddled on the streets of New York as novelties and the sight of the teeth alone could alarm cops.13

It is hard to emphasize just how much Roosevelt threw himself into the direct, personal improvement of his workforce:

Roosevelt’s midnight patrols left him sleepy because he rarely stopped for a nap before he went to work the following morning. [His wife] Edith disapproved of his grueling forty-hour patrol days, but she felt proud that when he took a cab home one night from an East Side meeting and he saw a policeman sitting down, smoking, rather than patrolling, he “sprang from the cab & administered a rebuke on the spot.”14

Praise and plaudits for good work

The part played by the recognition and reward of actual personal prowess among the members of the police force in producing [decreased crime] was appreciable.15

Anyone who has had a job knows the importance of recognizing good work. If you don’t do it, the employees who perform well will feel unappreciated and taken advantage of. Roosevelt understood this perfectly, and instituted a formal system of award and recognition:

During our two years’ service we found it necessary over a hundred times to single out men for special mention because of some feat of heroism. The heroism usually took one of four forms: saving somebody from drowning, saving somebody from a burning building, stopping a runaway team [of horses], or arresting some violent lawbreaker under exceptional circumstances.16

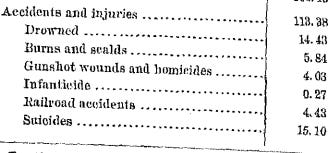

Side note: Interestingly, Roosevelt highlights one case of recognizing an officer who had saved twenty-five people from drowning in his autobiography. That, in addition to Roosevelt mentioning drowning as common cause for police heroics, made me curious—that seems like a lot of drowning, and far more than today! So I looked up death statistics for New York City in the 1890 census, and found my answer in Table 30 (deaths per 100,000 of the white population of NYC):

That’s comparable to the current nationwide death rate in automobile crashes, at just short of 14 per 100,000, and much higher than the current nationwide drowning death rate of <2 per 100,000. Drowning was much more common in the past than it is now!

New technology and methods

Roosevelt introduce a variety of new technologies to the police force:

🚲 Bicycles!

The members of the bicycle squad, which was established shortly after we took office, soon grew to show not only extraordinary proficiency on the wheel, but extraordinary daring. They frequently stopped runaways, wheeling alongside of them, and grasping the horses while going at full speed; and, what was even more remarkable, they managed not only to overtake but to jump into the vehicle and capture, on two or three different occasions, men who were guilty of reckless driving, and who fought violently in resisting arrest.17

🔫 Pistols!

One of the things that we did while in office was to train the men in the use of the pistol. A school of pistol practice was established, and the marksmanship of the force was wonderfully improved.18

☏ Telephones!

Roosevelt had a network of call boxes installed throughout city streets that connected police officers back to their station houses, which radically improved responsiveness and operational efficiency.19

🎞️ Photos & Fingerprints!

TR brought the Bertillon identification system, which featured the now-classic two-panel “mug shot,” to New York City. He later incorporated fingerprinting into the police arsenal.20

Character and Culture

On top of his demands for personal strength, courage, and fitness for the role of a police officer, Roosevelt believed in the equality of man, and judging individuals based on their character alone. He extended this belief fully in his police work, and there’s one particular instance that highlights it well. In a sort of proto-Skokie, here’s what happened when an anti-semitic preacher came to town:

The many-sided ethnic character of the force now and then gives rise to, or affords opportunity for, queer happenings. Occasionally it enables one to meet emergencies in the best possible fashion. While I was Police Commissioner an anti-Semitic preacher from Berlin, Rector Ahlwardt, came over to New York to preach a crusade against the Jews. Many of the New York Jews were much excited and asked me to prevent him from speaking and not to give him police protection. This, I told them, was impossible; and if possible would have been undesirable because it would have made him a martyr. The proper thing to do was to make him ridiculous. Accordingly I detailed for his protection a Jew sergeant and a score or two of Jew policemen. He made his harangue against the Jews under the active protection of some forty policemen, every one of them a Jew!21

TR’s war on vice, and his evenhanded law enforcement

In line with the rest of the Progressive era, TR disapproved of “vice”: gambling, drunkenness, prostitution, and the opportunities for blackmail, graft, and corruption these opened due to their illegality. He brought the full hammer of the law down on all of them, raiding saloons, gambling houses, houses of ill repute, and more.

His campaign to close saloons on Sunday—which was already required by law, but not uniformly enforced—especially angered many citizens of New York.

One could say a lot about his efforts here, but the notable aspect about all of them is: he pursued an even, uniform enforcement of existing law. He pursued it against the rich and poor, the politically powerful and the powerless, across ethnicities, and even across the sexes.

However much a modern sensibility would disapprove of his “policing morals,” his approach to the law was commendable, and a stark departure from the selective-enforcement-to-extract-bribes approach of his predecessors. He also wasn’t wrong on the object level of his policing. For example: alcohol was a scourge in New York, and too many men were getting too drunk too regularly. When he closed down saloons, “hospitals reported fewer alcohol-related injuries” and letters flew in from mothers and wives in tenements thanking them for their sober husbands. “The warden of Bellevue Hospital reported, two or three weeks after we had begun, that for the first time in its existence there had not been a case due to a drunken brawl in the hospital all Monday.”22

But these fights, despite winning him strong allies, would eventually make him eager to move on from the police department in 1897. His wife Edith observed that he never looked as harried or beaten down as when he was police commissioner, not even in the White House—but that’s because the police commissionership taught him how to balance the competing demands and frustrations of a prominent policy implementation role. Roosevelt had learned a lot, and would carry it far forward in service of the nation:

There was in New York City a strong sentiment in favor of honesty in politics; there was also a strong sentiment in favor of opening the saloons on Sundays; and, finally, there was a strong sentiment in favor of keeping the saloons closed on Sunday…Moreover, among the people who wished the law obeyed and the saloons closed there were plenty who objected strongly to every step necessary to accomplish the result, although they also insisted that the result should be accomplished.23

TR’s legacy

Unlike George Waring, whose street sweeping accomplishments would be his last (he died in 1898 at 65), TR had a long career ahead of him after he left the New York City police department. In order, he served as:

Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Governor of New York

Vice President of the United States

President of the United States

The changes he affected as president of the police board of commissioners did leave a mark—the department had more efficient finances, more and better police officers, upgraded technology, and improved reputation—although they wouldn’t last quite like Waring’s in sanitation. His relentless dedication to merit-based hiring, especially, waned in the very next mayoral administration.

He would remain dedicated to the cause of New York City police reform though, and as governor signed the bill that reorganized the department under a single commissioner responsible to the mayor—instead of the four-person board on which he served.

And finally, for any would-be civic reformer reading this, TR left a model for change. His massive action—the sheer dedication of his own time and energy beyond the level of a “regular job”—moved the needle immensely. Like Waring, he concretely demonstrated that his department could be reformed, despite the naysayers, and he would inspire many reformers who came after him.

Supplemental bibliography for further reading

Lexow, Clarence, and Cantor, Jacob Aaron. Report and Proceedings of the Senate Committee Appointed to Investigate the Police Department of the City of New York (1895).

Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, Chapter VI: “The New York Police,” (1913).

Dalton, Kathleen. Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life (2004).

Wallace, Mike, Burrows, Edwin. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (1999), pp.1200-1203.

H. Paul Jeffers. Commissioner Roosevelt: The Story of Theodore Roosevelt and the New York City Police, 1895-1897 (1994).

Note: opening pull quote is from page 187 of TR’s autobiography, from the chapter on his time with the New York police.

Golliher, Daniel. “Reformers backed William Lafayette Strong for mayor in 1894, and he brought in George Waring to head Street Cleaning,” How to Successfully Reform a Bureaucracy: George Waring & the Department of Street Cleaning (2024).

The plan was partly his, and partly that of his political friend and mentor, Henry Cabot Lodge: “Lodge urged TR to use his police work as a stepping-stone to statewide office, probably a Senate seat, then to aim for the presidency” A Strenuous Life (156).

Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, p.188-189.

Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, p.189-190.

Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life, p.151.

These would come back during his 1904 presidential campaign.

Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, p.201-202.

Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography, p.205-206.

Very interesting writeup that inspires me to read more about Teddy. The mental image of him and Riis personally catching errant bluecoats with mustaches drenched in incriminating foam is hilarious.