The Morality of Budgets: Goodharting and Denominator Blindness

In an era of overspending (much + badly spent), the moral valence of more spending is usually negative

“A budget is a moral document.”

This is a popular phrase for politicians and civic personalities in New York and around the United States. Its basic meaning is clear: what you fund is what you value. It doesn’t matter what you say you value—put your money where your mouth is.

In a basic sense, I agree with this. If the people’s representatives make a budget that funds X over Y, then they value X more as a function of government expenditure. It doesn’t matter how much they praise Y; we can see that what they actually do when monetary push comes to shove.

However, this phrase encourages two failure modes that reinforce each other:

Valuing the mere expenditure of more money, and not the results of that money (“line go up, never make line go down”). Aka: Goodhart’s law: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” People conflate “spending more money on something” with “getting more and better of that thing.”

Denominator blindness, which precludes financial prioritization. Hardly anyone contextualizes the budget in terms of its total value, or the total value of its discrete segments compared to each other. This allows everyone to complain that they’re underfunded compared to other overfunded departments—and no one checks denominators to see what’s true!

Failure mode #1: Goodharting the NYC budget

The largest open secret in New York City budgeting is that we spend more on education than anything else by a long shot—the Department of Education swallows at least a third of the city’s expense budget by itself, and there is no close second-place competitor. In practice, this means $35-40 billion a year out of a budget that clocks in around $110-115 billion.

💡 The most recently adopted city budget is here.The kicker: we don’t really get great results for that money in either the city or state:

Given these middling results and the $89 billion New York School districts will spend this year—with $39 billion coming from the State budget—it is disappointing that education policy reform efforts have not focused on examining and rectifying New York’s unsatisfactory performance. Instead, the debate is mostly centered on increasing State school aid even more and modestly shifting how dollars are allocated.

I’ve spoken about this with current, former, and prospective members of the government, as well as many members of the public. The near universal response to this information is a reliable two-step operation:

They are surprised to learn this, and didn’t know how much we were spending on education before, let alone how it compared to other jurisdictions (it doesn’t really compare—we’re in an expensive league of our own!).

They immediately get kind of mad at me, and I can see their facial muscles tensing as they label me an ideological suspect.

The second point usually happens because my interlocutor has been Goodharted—mere spending is their mental model for good and bad in a budget (at least for their favored causes), not spending relative to results. They suspect that I think we should “cut” educational spending, which in their world is only a bad thing:

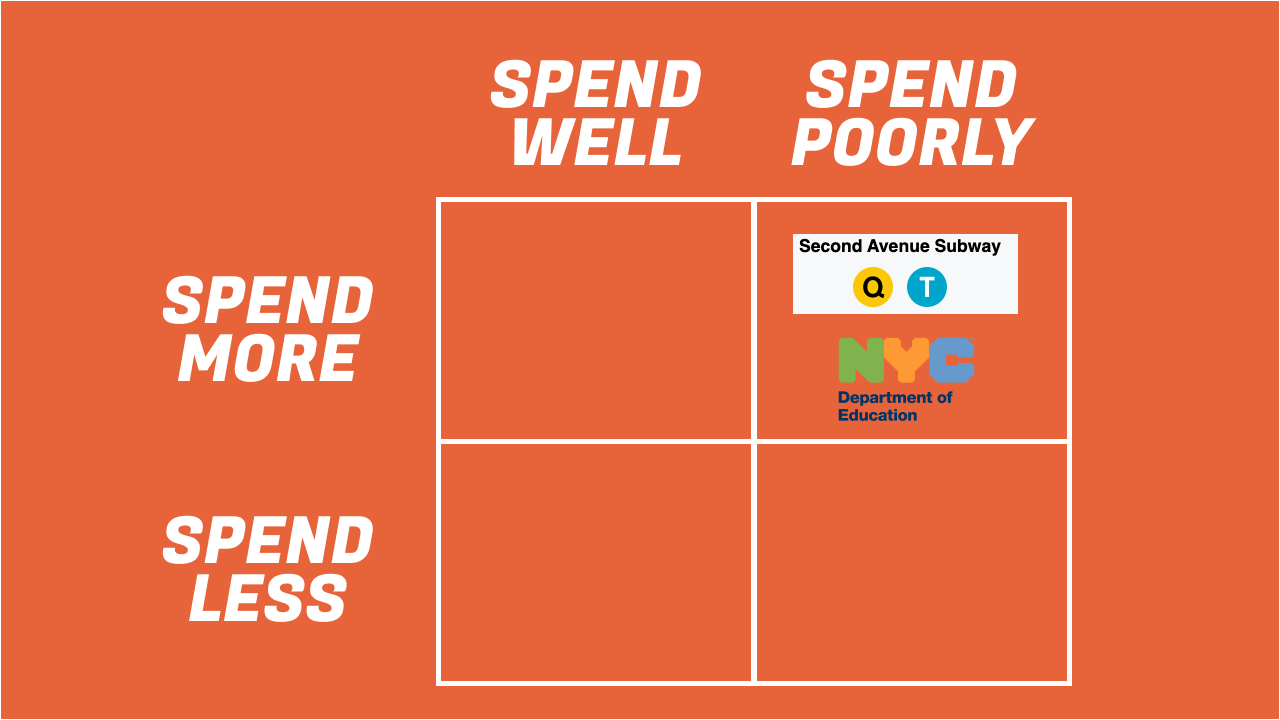

Of course this model is wrong if your goal is to get a certain kind of result from government spending. A better model would be rendered with two axes, spending and spending quality. This model prizes spending relative to results:

Thankfully we’ve started to see a shift in New York’s political world away from the one-axis, Goodhart model of spending, to the two-axis model that grades spending against results. For one example, see City Council Member Chi Ossé’s video about MTA spending:

Nonetheless, most budget discussions remain caught in the one-axis “more spending is always good” trap. This is probably more true for our education budget than anywhere else, and conversations about educational spending remain mired in the kind of hazy moralism that is inherently suspicious of trying to spend money well. People are even suspicious of retaining top-line budget numbers (~$35-40 billion), but reconfiguring the pattern of expenditure so that it actually gets better results (which will involve cutting spending somewhere sub-top-line).

Failure mode #2: Denominator blindness and failure to prioritize

Ask yourself: How much does NYC spend on various departments, and what are the top three most expensive ones? Do you know off the top of your head?

If, somewhere in your answer, you said something like “The police are the most expensive,” you are a victim of denominator blindness and advocates who have been less than forthcoming about city expenditures.

Although you can slice NYC’s expense budget up in multiple ways, the top three most expensive parts are:

Department of Education (~$32+ billion)

Department of Social Services (~$12+ billion)

NYPD (~$6+ billion)

This would seem to match many people’s stated preferences about proper spending allocation, but most of those people are unaware that their spending preferences are currently being matched in raw numbers.

💡 One reason why it’s a good idea to know the broad budget breakdown: it’s a quick bullshit detector. You can see who’s serious, and who’s not. You can see who knows the basics, and who doesn’t. No matter your political valence, you should want competent budget advocates who know what they're doing. All three of these numbers go up if you add in their fringe benefits and pension contributions, which are accounted for separately, but the ranking remains the same (although the NYPD jumps much closer to DSS).1 If you add in separate-but-related departments, these numbers explode upward by further billions, but still retain their ranking (for example, including the Department of Correction with NYPD, or Department of Homeless Services with DSS).

This top-3 ranking surprises almost everyone when they hear it, because it is almost always the first time anyone has told them the denominators of city expenditure. But if you’re in the failure mode of “a budget is a moral document,” denominators don’t matter. The only thing that matters is “spending go up.” And you simply never look for, or ask about, or think about, denominators. They’re not relevant!

Unfortunately, if people are not frank about denominators, it’s much harder to talk about budget priorities in a good way. And phrases like “they’re cutting the education budget by $10 million” and “they’re adding $100 million to the NYPD budget” do not take on their proper meaning. People only see the numerators, and measure them relative to their personal financial baseline—not the much larger baseline of New York City’s enormous budget.2

Are budgets moral documents?

Yes, but in an era of overspending (much + badly spent) they indicate depravity and waste, not dedication to producing more and better of the thing they fund.

Just as we have the replication crisis in science, we have an overspending crisis in government. In both cases, a lot of inputs (studies, funding) don’t generate productive results. In both cases, entrenched actors and regular people who have picked an actor-aligned tribe will get mad at you for trying to fix it. In both cases, those with the title of scientist and those who are budget advocates have been Goodharted to only chase more studies and more money, irrespective of results.

If you find yourself flinching away from the truth of plain budget numbers for any reason, consider why that is. Only a truthful, honest accounting of what we spend and how we spend it can get us into a better, more abundant future.

If I could wave a magic wand, I would like New York City to continue spending quite a lot of money—but it would buy far, far more. What if we spent $38 billion a year on education, but spent it well? New York would be the Athens of the world, and that is exactly the opportunity cost of our current poor spending regime.

As always, let me know if you want to have a good time working on things like this.

See section 2E of the adopted FY 2025 budget for the summary of department expenditures.

See section 110E-111E for the summary of pension contributions broken down by department (education takes the lion’s share).

See section 112E-114E for the summary of miscellaneous spending, like healthcare, social security payments, and more.

Of course, smaller amounts of money can be important independent of their larger departmental denominator. For example: if you were cutting the education budget by a few tens of millions by cutting off electricity to all schools, then you’ve killed the whole enterprise with just a small relative cut. However: this is not how the denominatorless people usually present our budget questions, and they still never tackle the elephant in the room of much/poor spending.

Budget as bs-detector is so true; I've noticed it at federal level when telling people DOD is not even close to mandatory spending, and it's an eye opener when they look up the numbers.

What are good reforms for education? Like what fat can be reallocated?